Christian Worship and the Natural World (Dr. Lisa Dahill)

LIFE IN ALL ITS FULLNESS:

CHRISTIAN WORSHIP AND THE NATURAL WORLD

Lisa E. Dahill

from Liturgy, 31 (4): 43–50, 2016

I have come that they may have life, and have it abundantly. (Jn 10:10, NRSV)

January 2014 saw a “polar vortex” throughout portions of North America: a jet-stream blockage to the west forced Arctic air farther south than is typical––well into Ohio, where I lived. My January course, Ecological Spirituality, met at Camp Mowana, an outdoor ministry site in Ohio located in terrain comprising the highest elevation of the state: chains of high hills across north-central Ohio, dividing the watersheds of the Ohio River to the south from Lake Erie in the north. The camp is situated at the confluence of two streams (Fleming Falls Run Creek and Chipmunk Creek), creating a landscape marked by ravines, small bluffs, and water sounds within a larger maple-beech woodland. The camp is home to coyote, deer, mink, raccoons, skunks, fish, amphibians, and water-insects in Chipmunk Creek and both local and migratory birds.

What does Christian worship have to do with the natural world? Everything, of course. We worship as bodies made from the amino acids, fats, minerals, and other elements derived from the plant cells, animal flesh, blood and juices, and chemicals interwoven in the food we eat; we worship a God incarnate in muscle, bones, nerves, veins, and tissues generated from first- century human DNA, whose mysterious wisdom gave rise to and permeates all that is; we worship through fluid, edible, drinkable means of grace, in sanc- tuaries built of arboreal flesh or hewn stone, windows fired clear to the sky, pews or chairs warm from the bodies of others. We use texts that sing of “rocks and springs, of skies and seas,” that pray of the cosmic expanse of this divine mystery in galaxies, rivers, and cells. We sing in collective intake and exha- lation of breath, oxygen released from the trees outside filling our lungs and blood vessels, carbon dioxide rushing back out to nourish more plant life.

What does Christian worship have to do with the natural world? Nothing, or very little, from the evidence of the greater number of hymns, liturgical texts, or prayers spilling out in the vast majority of Christian sanctuaries, in which the dominion of this God we worship is either cast in anthropocentric terms––concerned primarily or solely with human welfare––or implicitly located in a heaven separate from Earth, or both. If the natural world appears at all in Christian worship, it tends to be as backdrop for human actions, the stage set on which the real drama unfolds, or perhaps an occasional terror, as when natural disaster threatens human life. We may hear an annual sermon on climate change; and in Lutheran communities following the rubrics in Evangelical Lutheran Worship (ELW), we may more regularly hear and pray petitions for the creation. Yet I have learned that by far the most common response Christians give when they learn I am passionate about worship and the natural world is, “Really? There’s a connection?”

What does Christian worship have to do with the natural world?

Each day, small groups of students led outdoor morning prayer. They were asked to spend the first day at Camp Mowana exploring the terrain and getting to know its various places, features, and creatures, so that they could sense which locations called to them as places for the prayer they would lead and what kinds of prayer felt right in those locations. They were to design these short (15–20 minute) prayer times to respect not only the place/s they chose but also our bodies’ capacities within the seasonal context of extreme cold: during our stay the morning temperatures hovered around zero degrees Fahrenheit.

With many others, I am convinced that Christian worship is meant to participate in God’s mission of giving life to the world: to be a place where the Spirit brings into tangible reality the resurrection life and love poured out for all in Jesus Christ. I care deeply about the connections between wor- ship and this divine mission of love in human lives, communities, societies, and structures; and increasingly I am curious also about connections between Christian worship and the natural world. In my teaching, scholarship, and participation in worship, I have been pursuing these connections not pri- marily through strategies of bringing the natural world into indoor worship spaces (through textual imagery, physical artifacts, or architectural forms opening sanctuaries to their surroundings, although I also attend to all of these) but through moving the entire experience of Christian worship out. In summer 2012, a colleague and I designed and led an “indoor/outdoor” Eucharist to close the August gathering of the ELCA’s Association of Teach- ing Theologians, held that year at Capital University and Trinity Lutheran Seminary, where we were on the faculty. I described that service in the published proceedings of the conference.

The fact that the outdoors can be experienced as fully liminal, as existing within the fullness of the Christian worship experience proper, needs ritual attention in our era of overwhelmingly indoor experience––our lives played out in homes and vehicles and schools and offices, made increasingly all the more imprisoning through the layers of screens and “virtual” experience many worshipers live within for much of their everyday experience. To be in the unmediated outdoors, unplugged, intentionally and attentively open to the actual bodies and noises and movements of the broader creation, is an increasingly rare experience for many North Americans; to be so at the very heart of Christian worship is almost unheard of.1

And I continue to be fascinated with the question of what happens when Christian worship moves outdoors. How do liturgical speech and action shift when the space within which we worship is the larger world, not bounded by sanctuary walls? How does a worship location outdoors proclaim God’s love and embrace of this world differently from worship indoors? And how ought our ritual speech and action shift, if at all, in these outdoor wor- ship spaces?

This essay will explore these questions through primary attention to the final one. Moving worship outdoors does not, in and of itself, necessarily produce meaningful change in worshipers’ orientation to their surroundings (except perhaps to curse the wind, cold, heat, or mosquitoes and wish they were indoors). Inviting worshipers into conscious awareness of and relation- ship with the more-than-human world requires attention also to the content of our liturgies: neither mechanically reproducing outdoors what we do indoors (chairs in rows, electronic sound systems, unchanged texts) nor throwing out liturgy altogether. I am convinced that we need fully liturgical and poetic language, outdoors as well as in, and that the liturgical resources of Christian traditions provide scaffolding capable of generating language and gestures that are powerfully Christian and intimately––indeed bioregion- ally––contextual.2 I am curious to test the adequacy of one such contextuali- zation: my adaptation of the rite of Affirmation of Baptism in ELW, designed for use with my students at the icy confluence of Chipmunk and Fleming Falls Run Creeks.

Within the ongoing strands of the story of my class at Camp Mowana, this essay will first trace the meaning of “bioregionalism” and argue for Christian worship to be deeply grounded in place. Next, I will describe my proposal to move the practice of Christian baptism outdoors, along with associated rites such as Affirmation of Baptism: both to enact and to experience our christo- logical connection to our larger watershed through this primal sacrament. Third, I will assert that the obligation of truth-telling at the font3 obliges Christians to take up an interspecies contextualization of our liturgical texts. Finally, I will give an example of an urban seminary worship service that exemplifies my thesis: that Christian worship is meant to restore and invite humans into the fullness of life in a given place, for the healing of the whole.

The alienation from the larger life of the natural world described above is not unique to Christian worshipers. We participate in a larger social construc- tion of reality in much of the contemporary West in which attention to the native flora and fauna (the complex migratory patterns and hatching cycles, predator/prey relations and seasonal flowerings all unfolding within a given place’s larger water-cycles and climate patterns) is irrelevant to the daily functioning and pressing concerns of most older children, youth, and adults. Asked to name edible plants native to their area in a given season, or the proximate destination of the wastewater flowing down their drains, most Americans would be as flummoxed as the students to whom I sometimes address these questions.4 On such measures Christian worshipers are little different. We may be able to name the colors of the Christian feasts and seasons but only a minority knows what wildflower is the first to bloom in spring in particular woods or meadows. Even for those who do, such knowl- edge is rarely considered central to the faith.

Christians generally assert that the scope of the world’s redemption in Christ includes all creation. What would it look like if our worship actually reflected such a claim? Like its surrounding terrain, I believe, Christian worship would be bioregionally diverse. The language of “bioregionalism” has emerged in the last forty years or so as a collection of biologists, philosophers, writers, and activists has urged returning perceptual attention and our analy- sis and action to local bioregions. Kirkpatrick Sale defined the term in this way in 1985: “Bio is from the Greek word for forms of life ... and region is from the Latin regere, territory to be ruled ... . They convey together a life-territory, a place defined by its life forms, its topography and its biota, rather than by human dictates; a region governed by nature, not legislature. And if the con- cept initially strikes us as strange, that may perhaps only be a measure of how distant we have become from the wisdom it conveys.”5 If Christians are to be leaders in reorienting privileged humans back to the larger endangered world from which our economy and social patterns have alienated us, then our worship must surely be the central place both modeling and inviting us into attentive relationship with our watersheds.6 We must––that is––be baptized literally back into them.

Thus I have come to sense that the church may have lost more than it gained when, for understandable reasons, it gradually moved the location of this primal sacrament from its original outdoor location in “living”—that is, flowing––local waters into specially constructed baptisteries, and from there into fonts. That movement indoors made the practice of baptism simpler in many ways, even as it also shifted the register of the sacrament, making possible greater dimensions of human symbolic artistry in the con- struction and adornment of those baptisteries and fonts, and the accompany- ing elaboration of associated baptismal rites. Indoor practice allowed the development of the rite toward experiences of womb-like watery enclosure, the layering of sensory symbols and aesthetic liminality in dramatic midnight Easter Vigils. Its relative physical safety can help midwife a vulnerability of spiritual stripping and rebirth to transforming effect.

Yet in this movement indoors, the rite lost a primary dimension of its original symbolic power, a dimension inseparable from the ecological crisis our species faces today. The abandonment of local rivers, creeks, oceans, or springs as the prized location for this comprehensive symbolic enactment of the meaning of Christian faith has also made possible and continues to reinforce the anthropocentric and at times radically otherworldly shape of Christian faith and piety through the centuries.

Liturgical theologians are increasingly pointing to the symbolic and literal inseparability of baptismal water and the actual hydrology of one’s watershed. Rites of pouring into the font with water gathered from local (or faraway) water sources, the naming of local waters in the prayers at the font––becoming prayerfully conscious of the real sources of these real waters––are all to the good. Yet, when enacted indoors, even these and other salutary practices do not fully overcome the separation of this rite from those actual waters.

On the last day of our time at Camp Mowana, our class moved out in the mid- morning chill, four degrees Fahrenheit, for our closing baptismal affirmation.

Responding to Pope Francis’s recent call for “ecological conversion” on the part of all Earth’s people, I have proposed that a primary symbolic way Christians can enact our redemptive joining to the boundless interpermeation of the “wild Logos” and all that exists (Jn 1:1–5) is to restore the early church practice of baptizing into local waters.7 The proposal has a number of dimen- sions: from concerns about pollution and the baptismal urgency of fighting to clean and protect local waters, to stories of the exhilaration of such risky public practice in particular places. I continue to be convinced that no single movement toward the ecological conversion Francis calls for is as symboli- cally powerful as outdoor baptismal practice, immersing Christians from all traditions into the astonishing, oxygenated water-life we share with multi- tudes of visible and invisible interspecies kin, our sisters and brothers in a much larger body of Christ:

Restoring the practice of baptism outdoors thus dramatically broadens... the meaning of being Christian: not excluding the personal and human- communal levels of spiritual meaning, but extending those to include now also one’s spiritual incorporation into experienced immersive kinship with the larger biological community in which one lives and into the hydrological cycle of the Earth itself, its jeopardy and beauty. Thus being Christian comes to mean, also, baptized into the full wildness of the world and its flourishing, and into this particular degraded or intact watershed. It is utterly immersive.8

In the paper first outlining this proposal, I did not yet, however, address the question of the texts used at such outdoor rites.

When we arrived at the creeks’ confluence, I began the rite. The ELW profession of faith includes a threefold renunciation of evil. In adapting this rite, I expanded each of these renunciations to name dimensions of evil we had been discussing through our two weeks of intensive study, debate, and discussion. The first ELW renunciation reads, “Do you renounce the devil and all the forces that defy God?” I expanded this text, asking, “Do you renounce the devil, injustice, pride, mindlessness, greed, idolatry, affluence, complacency, the fossil fuel industry, and all the forces that destroy God’s creation? If so, please answer, ‘I renounce them!’” The two subsequent renun- ciations similarly allowed the students a ritual way to claim within their baptismal vocation core dimensions of an ecological faith.

At the profession of the Apostles’ Creed, I also expanded each article (and, in the case of the first article, adapted the text as well) to ask, “Do you believe in God, Source and Wellspring, Creator of heaven and Earth, alive with interrelationship, beauty, hope, balance, diversity, strangeness, interdependency, wasps, goats, croco- diles, rivers and oceans and streams and ice, the communion of all beings, stars thick as rain above us day and night, and also useless pleasure? If so, please answer, I do!” Once again, the additional terms I added––strangeness, goats, crocodiles, etc.––were not randomly chosen but drawn directly from course material (or, in the case of the goats, from the barn at the camp itself).9

Following this twice-threefold profession, and a slightly modified (toward creation) set of baptismal promises, we continued in pairs with a lovely ELW rite for marking catechumens’ bodies with the sign of the cross on each other’s eyes, ears, lips, shoulders, heart, hands, and feet using text I again adjusted lightly to orient our vision, hearing, speaking, bearing, etc., toward the fullness of Earth’s life.10 From the joyful vociferous responses in the profession of faith, this crossing of stocking-capped ears, mittened hands, and heavy-booted feet took on an increasingly playful tone, and by the time I invited participants at the end to asperge one another with snow, the proceedings moved into exhilarated hilarity.

This rite began to teach me what previously I had only sensed: that wor- ship, especially the sacraments, works by inviting worshipers into the largest possible relationships between all that exists: this snow, these trees, these crea- tures and the humans playing, and the air, the wind, the faraway cars on the interstate, carbon and oxygen and animal quickening, the water and word per- meating it all ... out here, in the cold, in the world, we are reborn into reality. We are returned to our kinship with the lives of all that is. And the texts we use need to reflect that reality. David Batchelder insists that ritual speech works only when it tells the deepest truth of participants’ lives: “I worry that our communities have learned to practice a way of speaking ritually that not only permits false witness at the font, but establishes it as the norm. We make claims concerning sin and evil but often live as if we have not really con- sidered the implications.”11 A key part of the solution, Batchelder asserts, is to reclaim the invitation given in contemporary ritual frameworks, with solid historical precedent, to expand the baptismal renunciations toward naming particular forms of evil threatening participants’ own fullness of life.12 My proposal in this essay goes further, to include in creedal profession also the naming of particular forms of life from which our privilege has alienated us.

Christian ritual needs to help us tell the truth at the font of our bioregional Christological life and thereby invite us more fully into reality, as that reality is threatened and effaced in the world today. Christians’ awakening to the fullness of our interspecies life requires explicitly and unapologetically inter- species liturgical language––even or perhaps especially in the affirmation of reality crystallized in creedal profession, with any added content varying according to bioregion and watershed. The textual adaptation I outline in the Mowana story illustrates my conviction that baptism and the baptismal life have bioregionally diverse meanings, shape, and relationships––and that these relationships in their specificity need honoring in our holiest ritual texts precisely because without such naming we simply do not see and notice them. The naming of creatures alive in your watershed requires knowing who they are. Such knowing involves attentive, intensive immersion in that watershed, with others, over time.

Such ritual naming then invites those we name into the larger world of Christian relationship, just as it invites us into conscious kinship with them. This corresponds to the kind of naming of the participants themselves that takes place in the affirmation rite; here many other creatures turn out to belong within the larger tapestry of reality permeated by Christ (both biore- gionally specific and cosmologically expansive) into which Christian baptism invites us. What would the Affirmation of Baptism––in the form known as Confirmation––look like if it took place not indoors on a padded carpet but in expansive, playful, profound improvisation with these confirmands and the muddy, edgy, wild life of your own community’s waterways? What if its ritual language allowed those affirming not only to make their own the ancient and holy words, gestures and contours of the faith, but also to claim and affirm the fragile and sustaining relationships with local spring frogs, wildflowers, herons, or coyotes?

Such moves are dangerous for many reasons, not least that baptismal kinship with all the creatures outside our doors includes also those humans we will meet when our worship ventures into our larger waters, streets, and watershed. A student from the Ecological Spirituality course, Justin Ferko, was inspired both from that course and from his call to street-church ministry to design for the seminary’s worship a further adaptation of this watershed rite. Working on a Lenten weekday chapel service––in a February 2015 week of very cold temperatures––Justin led us to process from the seminary to the edge of the nearby creek, to affirm our baptismal vocation in communion with all who live outdoors in the watershed including humans who had died of exposure to the elements in the last year (one whose funeral was taking place that very evening). I adapted the baptismal affirmation pieces along the lines first used at Mowana, edited here for our urban watershed. But the lines that stick with me from are from Justin’s prayer.

Here on the banks of Alum Creek we remember our baptism and the grace of God who loves all of creation. We are in the presence of living water in a riparian zone that flows through our community full of life: fish, mussels, bats, osprey, wood frogs, squirrels, raccoons, deer, sycamore, maple, and beech and people.

We acknowledge the human impact on this environment with pollution, elevated levels of cadmium, arsenic, and zinc in its sediment and overflow from salt-treated roads, landfills, and industry. We acknowledge our sin against one another as we remember Cloria and Lorenzo who died on the banks of this creek. We continue praying for Michael whose funeral is this evening.13

Justin’s rite honors Pope Francis’s call not only to ecological conversion but also to “integral ecology”: the reality that this prayer outdoors, in wild communion with all who live in our watershed, will draw us necessarily also into relationship and advocacy for the children of God of all species including our own.14

“With you, O Lord, is life in all its fullness,” sings the Taizé chant inspired by Psalm 36:9. What does Christian worship have to do with the natural world, with the mussels and salamanders, mink and sycamores of Alum Creek, with the humans who live outdoors––near your home or across the world––and the creatures of every watershed? The more I learn of this wild abundance, the bigger worship becomes. Surely, with all of it, baptismal life and worship have everything in the world to do.

#

Notes

1. Lisa E. Dahill, “Indoors and Outdoors: Praying with the Earth,” in Eco-Lutheranism, ed. Shauna Hannan and Karla Bohmbach (Minneapolis: Lutheran University Press, 2013), 118. The worship tak- ing place at outdoor ministry sites around the country is a powerful counter-example to this assertion; its formative role in the faith of Christians has much to do with its invitation into extended time outdoors.

2. S. Anita Stauffer, ed., Christian Worship (Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, 1996), 23–28. The Nairobi Statement asserts that Christian worship relates dynamically to culture by being transcul- tural, contextual, counter-cultural, and cross-cultural. I am exploring the contextual aspect as it relates to the local bio-region.

3. This language prefigures attention to the writing of David Batchelder later in the essay.

4. Readers can test their own bioregional knowledge at sites like this one: https://indigenize. wordpress.com/2013/03/21/bioregional-quiz/.

5. Kirkpatrick Sale, Dwellers in the Land (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1985), 43.

6. I am grateful for Ched Myers’s work and vision as a pioneer in “watershed discipleship”–– learning to practice Christian life in relationship with the creatures, forces, and features of one’s actual local watershed. See “From ‘Creation Care’ to ‘Watershed Discipleship’: Re-Placing Ecological Theology and Practice,” Conrad Grebel Review 32, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 250–75. Myers, 258: John Wesley Powell gave us a classic definition of watership in 1875 when he wrote that “a watershed is that area of land, a bounded hydrologic system, within which all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they become part of the community.”

7. Lisa E. Dahill, “Into Local Waters: Rewilding the Study of Christian Spirituality” (Presidential Address presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Christian Spirituality, Atlanta, GA, 20 November 2015), forthcoming in Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality (Fall 2016). The address develops this language of the “wild Logos”––through whom all things were made––as a christological reference point for the practice of outdoor baptism. For Pope Francis’s call to ecological conversion, see Laudato Si’, On Care for Our Common Home (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2015), 216–21ff. Of course, some Christians have never left these riverbanks: from African-American communities in the U.S. rural South to Orthodox Christians around the world celebrating Epiphany, worshipers in many places still perform powerful baptismal and related rites in and with their local waters. See, for instance, Nicholas E. Denysenko, The Blessing of the Waters and Epiphany (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2012).

Dahill, “Into Local Waters,” pages 12–13 of the paper as delivered.

I do not change rites simply for the sake of novelty. In teaching worship at Trinity I emphasized tirelessly with my students never to force or expect people to speak ritual words without adequate, ideally profound, preparation. Thus in narrating the above story, I caution the reader that to take my adaptation directly into one’s own context does a grave disservice to that context and community. Ritual adaptation makes powerful sense only when it emerges directly from a particular community’s recognizable and meaningful discourse and from the actual creatures and forces of the living world outside the community’s own doors.

Evangelical Lutheran Worship: Leaders Desk Edition (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2006), 594.

David B. Batchelder, “Baptismal Renunciations: Making Promises We Do Not Intend to Keep,” Worship 81 (September 2007): 411.

12. Ibid., 421–23. His essay notes these precedents.

13. Justin Ferko, leaders’ guide, chapel service February 26, 2015, Trinity Lutheran Seminary, Columbus, OH.

14. Laudato Si’, chap. 4, 137–62.

###

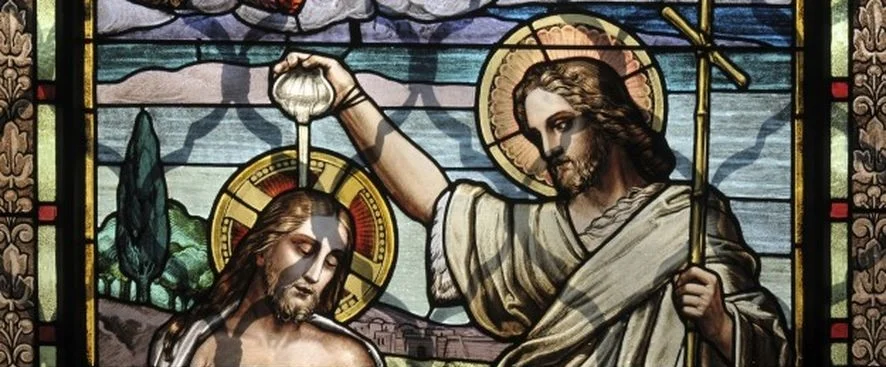

Cover image by Rev. Carmen Retzlaff.

Lisa E. Dahill is assoc. professor of religion at California Lutheran University. See more of her writings here.